“The essence of strategy is choosing what not to do.” – Michael Porter

In 2021, a major real estate data company shut down its multi-billion-dollar “iBuying” business after its predictive algorithm failed spectacularly in a volatile market. Around the same time, an online eyewear retailer’s routine search bar upgrade, intended as a minor cost-saving measure, unexpectedly increased search-driven revenue by 34%, becoming the company’s most effective salesperson.

Why do some technology initiatives produce transformative value while others, with similar resources, collapse? The outcomes are not random. They are a direct result of the conditions under which a project begins – the clarity of its goals, the nature of its risks, and the predictability of its environment.

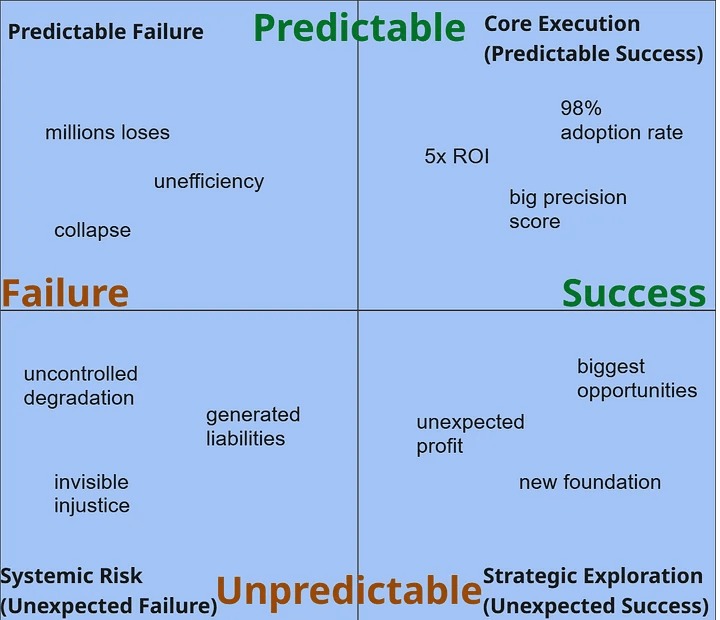

To understand these divergent results, this analysis introduces the Initiative Strategy Matrix – a simple four-quadrant framework for classifying technology projects. It’s an analytical tool to help categorize case studies and distill actionable insights. By sorting initiatives based on whether their outcomes were predictable or unpredictable, and whether they resulted in success or failure, we can identify the underlying patterns that govern value creation and destruction.

Our analysis sorts projects into four distinct domains:

- Quadrant I: Core Execution (Predictable Success). Where disciplined execution on a clear goal delivers reliable value. This is the bedrock of operational excellence.

- Quadrant II: Predictable Failure. Where flawed assumptions and a lack of rigor lead to avoidable disasters. This is the domain of risk management through diagnosis.

- Quadrant III: Strategic Exploration (Unexpected Success). Where a commitment to discovery produces breakthrough innovation. This is the engine of future growth.

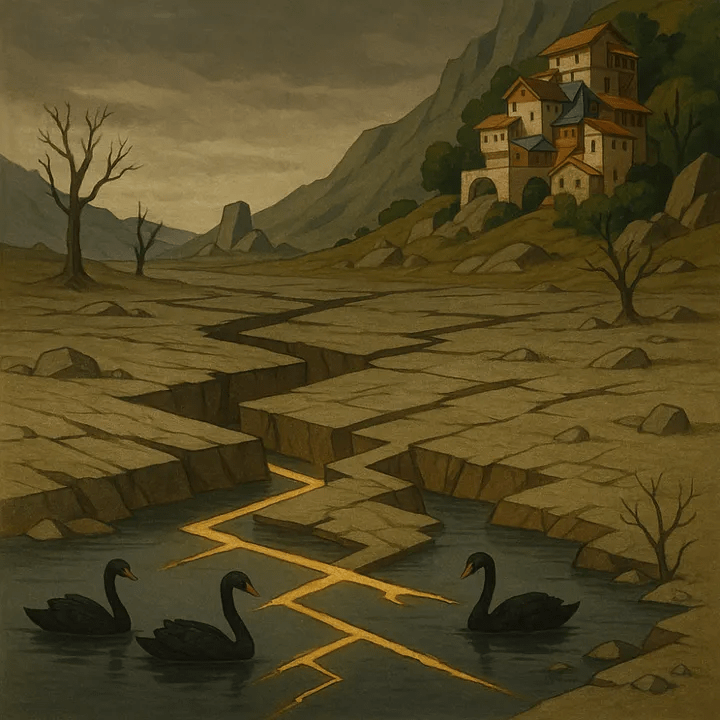

- Quadrant IV: Systemic Risk (Unexpected Failure). Where hidden, second-order effects trigger catastrophic “black swan” events. This is the domain of risk management through vigilance.

The following sections will explore each quadrant through detailed case studies, culminating in a final summary of key lessons. Our analysis begins with the bedrock of any successful enterprise: Quadrant I, where we will examine the discipline of Core Execution.

Quadrant I: Core Execution (Predictable Success)

“The first rule of any technology used in a business is that automation applied to an efficient operation will magnify the efficiency. The second is that automation applied to an inefficient operation will magnify the inefficiency.” – Bill Gates

Introduction: Engineering Success by Design

This chapter is about building on solid ground. Quadrant I projects are not about speculative moonshots; they are about the disciplined application of AI to well-defined business problems where the conditions for success are understood and can be engineered. These are the initiatives that build organizational trust, generate predictable ROI, and create the foundation for more ambitious AI work.

We will dissect the anatomy of these “expected successes,” demonstrating that their predictability comes not from simplicity, but from a rigorous adherence to first principles. For any team or leader, this quadrant is the domain for delivering reliable, measurable value and building organizational trust.

The Foundational Pillars of Quadrant I

Success in this quadrant rests on four pillars. Neglecting any one of them introduces unnecessary risk and turns a predictable win into a potential failure.

- Pillar 1: A Surgically-Defined Problem. The scope is narrow and the business objective is crystal clear (e.g., “reduce time to find internal documents by 50%,” not “improve knowledge sharing”).

- Pillar 2: High-Quality, Relevant Data. The project has access to a sufficient volume of the right data, which is clean, well-structured, and directly relevant to the problem. Data governance is not an afterthought; it is a prerequisite.

- Pillar 3: Clear, Quantifiable Metrics. Success is defined upfront with specific, measurable KPIs. Vague goals like “improving user satisfaction” are replaced with concrete metrics like “increase in average order value” or “reduction in support ticket resolution time.”

- Pillar 4: Human-Centric Workflow Integration. The solution is designed to fit seamlessly into the existing workflows of its users, augmenting their capabilities rather than disrupting them.

Case Study Deep Dive: Blueprints for Value

We will now examine three distinct organizations that masterfully executed on the principles of Core Execution.

Case 1: Morgan Stanley – The Wisdom of a Thousand Brains

The Dragon’s Hoard

Morgan Stanley, a titan of wealth management, sat atop a mountain of treasure: a vast, proprietary library of market intelligence, analysis, and reports. This was their intellectual crown jewel, the accumulated wisdom of thousands of experts over decades. But for the 16,000 financial advisors on the front lines, this treasure was effectively locked away in a digital vault. Finding a specific piece of information was a frustrating, time-consuming hunt. Advisors were spending precious hours on low-value search tasks – time that should have been spent with clients. The challenge was clear and surgically defined: how to unlock this hoard and put the collective wisdom of the firm at every advisor’s fingertips, instantly.

Forging the Key

The firm knew that simply throwing technology at the problem would fail. These were high-stakes professionals whose trust was hard-won and easily lost. A clunky, mandated tool would be ignored; a tool that felt like a threat would be actively resisted. The architectural vision, therefore, was as much sociological as it was technological. In a landmark partnership with OpenAI, they chose to build an internal assistant on GPT-4, but the implementation was a masterclass in building trust.

The project team held hundreds of meetings with advisors. They didn’t present a finished product; they asked questions. They listened to concerns about job security and workflow disruption. They co-designed the interface, ensuring it felt like a natural extension of their existing process. Crucially, they made adoption entirely optional. This wasn’t a new system being forced upon them; it was a new capability being offered. The AI was framed not as a replacement, but as an indispensable partner.

The Roar of Productivity

The outcome was staggering. Because the tool was designed by advisors, for advisors, it was embraced with near-universal enthusiasm. The firm achieved a 98% voluntary adoption rate. The impact on productivity was immediate and dramatic. Advisors’ access to the firm’s vast library of documents surged from 20% to 80%. The time wasted on searching for information evaporated, freeing up countless hours for strategic client engagement.

The Takeaway: In expert domains, trust is a technical specification. The success of Morgan Stanley’s AI was not just in the power of the Large Language Model, but in the meticulous, human-centric design of its integration. By prioritizing user agency, co-design, and augmentation over automation, they proved that the greatest ROI comes from building tools that empower, not replace, your most valuable assets. The 98% adoption rate wasn’t a measure of technology; it was a measure of trust.

Case 2: Instacart – The Ghost in the Shopping Cart

The Cold Start Problem

For the grocery delivery giant Instacart, a new user was a ghost. With no purchase history, a traditional recommendation engine was blind. How could it suggest gluten-free pasta to a celiac, or oat milk to someone lactose intolerant? This “cold start” problem was a massive hurdle. Furthermore, the platform was filled with “long-tail” items – niche products essential for a complete shopping experience but purchased too infrequently for standard algorithms to notice. The challenge was to build a system that could see the invisible connections between products, one that could offer helpful suggestions from a user’s very first click.

Mapping the Flavor Genome

The Instacart data science team made a pivotal architectural choice: instead of focusing on users, they would focus on the products themselves. They decided to map the “flavor genome” of their entire catalog. Using word embedding techniques, they trained a neural network on over 3 million anonymized grocery orders. The system wasn’t just counting co-purchases; it was learning the deep, semantic relationships between items. It learned that “tortilla chips” and “salsa” belong together, and that “pasta” and “parmesan cheese” share a culinary destiny. Each product became a vector in a high-dimensional space, and the distance between vectors represented the strength of their relationship. They had, in effect, created a semantic map of the grocery universe.

From Ghost to Valued Customer

The results were transformative. The new system could now make stunningly accurate recommendations to brand-new users. The “ghost in the cart” became a valued customer, guided towards relevant products from their first interaction. The model achieved a precision score of 0.59 for its top-20 recommendations – a powerful indicator of its relevance. Visualizations of the vector space confirmed it: the AI had successfully grouped related items, creating a genuine semantic understanding of the grocery domain.

The Takeaway: Your core data assets, like a product catalog, are not just lists; they are worlds of latent meaning. By investing in a deep, semantic understanding of this data, you can build foundational technologies that solve multiple business problems at once. Instacart’s product embeddings didn’t just improve recommendations; they created a superior user experience, solved the cold start and long-tail problems, and built a system that was intelligent from day one.

Case 3: Glean – The Million-Dollar Search Bar

The Productivity Tax

At hyper-growth companies like Duolingo and Wealthsimple, success had created a new, insidious problem. Their internal knowledge – the lifeblood of the organization – was scattered across hundreds of different SaaS applications: Slack, Jira, Confluence, Google Drive, and more. This fragmentation created a massive, hidden productivity tax. Employees were wasting hours every day simply trying to find the information they needed to do their jobs. For Wealthsimple’s engineers, it meant slower incident resolution. For Duolingo, it was a universal drag on productivity during a period of critical expansion. The problem was well-defined and acutely painful: they needed to eliminate the digital friction that was costing them a fortune.

The Knowledge Graph and the Guardian

Both companies turned to Glean, an AI-powered enterprise search platform built to solve this exact problem. Glean’s architecture was two-pronged. First, it acted as a cartographer, connecting to over 100 applications to create a unified “knowledge graph” of the company’s entire information landscape. It didn’t just index documents; it understood the relationships between conversations, projects, people, and company-specific jargon.

Second, and most critically, it acted as a guardian. Glean’s system was designed from the ground up to ingest and rigorously enforce all pre-existing data access permissions. This was the non-negotiable requirement for enterprise success. An engineer could not see a confidential HR document; a marketing manager could not access sensitive financial data. The AI had to be powerful, but it also had to be trustworthy.

The ROI of Instant Answers

The implementation delivered a clear and defensible return on investment. The productivity tax was effectively abolished.

- Duolingo reported a 5x ROI, saving its employees over 500 hours of work every single month.

- Wealthsimple calculated annual savings of more than $1 million. Their Knowledge Manager was unequivocal: “Engineers solve incidents faster, leading to an overall better experience for everyone involved.”

The Takeaway: Data governance is not a barrier to AI; it is the essential enabler for its success in the enterprise. By solving a universal, high-pain problem with a targeted AI solution that robustly handled complex permissions, Glean demonstrated that the most powerful business case for AI is often the simplest: giving people back their time. For any team, this proves that building on a foundation of trust and security allows you to deliver solutions with a clear, predictable, and compelling financial upside.

The Quadrant I Playbook

Distilling the patterns from these successes, we can create a playbook for designing and executing projects in this quadrant.

- Step 1: Identify the High-Value, Bounded Problem. Find a “hair on fire” problem within a specific domain that is universally acknowledged as a drag on productivity or revenue.

- Step 2: Audit Your Data Readiness. Before writing a line of code, rigorously assess the quality, availability, and governance of the data required. Is it clean? Is it accessible? Are the permissions clear?

- Step 3: Define Success Like a CFO. Translate the business goal into a financial model or a set of hard, quantifiable metrics. This will be your north star and your ultimate justification for the project.

- Step 4: Design for Augmentation and Trust. Map the user’s existing workflow and design the AI tool as an accelerator within that flow. Involve end-users in the design process early and often.

- Step 5: Build, Measure, Learn. Start with a pilot group, measure against your predefined metrics, and iterate. A successful Quadrant I project builds momentum for future AI initiatives.

Conclusion: Building the Foundation

Quadrant I is where credibility is earned. By focusing on disciplined execution and measurable value, teams deliver predictable wins that solve real business problems. These successes are the foundation upon which an organization’s entire innovation strategy is built. They fund future exploration and, most importantly, build the organizational trust required to tackle more complex challenges.

However, discipline alone is not enough. When rigorous execution is applied to a flawed premise, it doesn’t prevent failure – it only makes that failure more efficient and spectacular. This brings us to the dark reflection of Quadrant I: the world of predictable failures.

Quadrant II: Predictable Failure

“Failure is simply the opportunity to begin again, this time more intelligently.” – Henry Ford

Introduction: Engineering Failure by Design

This chapter is a study in avoidable disasters. If Quadrant I is about engineering success through discipline, Quadrant II is its dark reflection: projects that were engineered for failure from their very inception. These are not ambitious moonshots that fell short; they are “unforced errors,” initiatives born from a lethal combination of hubris, technological misunderstanding, and a willful ignorance of operational reality.

They are the projects that consume enormous resources, erode organizational trust, and ultimately become cautionary tales. This quadrant is not about morbid curiosity. It is about developing the critical faculty for teams and leaders to identify these doomed ventures before they begin, protecting the organization from its own worst impulses. Here, we dissect the blueprints of failure to learn how to avoid drawing them ourselves.

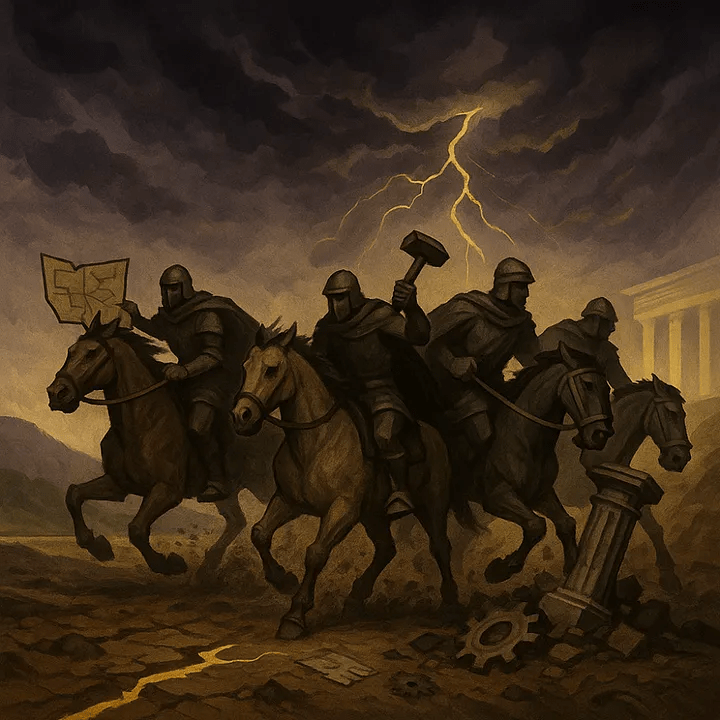

The Four Horsemen of AI Project Failure

Predictable failures are rarely a surprise to those who know where to look. They are heralded by the arrival of four distinct anti-patterns. The presence of even one of these “horsemen” signals a project in grave peril; the presence of all four is a guarantee of its demise.

- Horseman 1: The Vague or Grandiose Problem. This is the project with a scope defined by buzzwords instead of business needs. Its goal is not a measurable outcome, but a headline: “revolutionize healthcare,” “transform logistics,” or “solve customer service.” It mistakes a grand vision for a viable project, ignoring the need for a surgically-defined, bounded problem.

- Horseman 2: The Data Mirage. This horseman rides in on the assumption that the necessary data for an AI project exists, is clean, is accessible, and is legally usable. It is the belief that a powerful algorithm can magically compensate for a vacuum of high-quality, relevant data. This anti-pattern treats data governance as a future problem, not a foundational prerequisite, ensuring the project starves before it can learn.

- Horseman 3: Ignoring the Human-in-the-Loop. This is the failure of imagination that sees technology as a replacement for, rather than an augmentation of, human expertise. It designs systems in a vacuum, ignoring the complex, nuanced workflows of its intended users. The result is a tool that is technically functional but practically useless, one that creates more friction than it removes.

- Horseman 4: Misunderstanding Operational Reality. This horseman represents a fatal blindness to the true cost and complexity of deployment. It focuses on the elegance of the algorithm while ignoring the messy, expensive, and brutally complex reality of maintaining the system in the real world. It fails to account for edge cases, support infrastructure, and the hidden human effort required to keep the “automated” system running.

Case Study Deep Dive: Blueprints for Failure

We will now examine three organizations that, despite immense resources and talent, fell victim to these very horsemen.

Case 1: IBM Watson for Oncology – The Over-Promise

The Grand Delusion

In the wake of its celebrated Jeopardy! victory, IBM’s Watson was positioned as a revolutionary force in medicine. The goal, championed at the highest levels, was nothing short of curing cancer. IBM invested billions, promising a future where Watson would ingest the vast corpus of medical literature and patient data to recommend optimal, personalized cancer treatments. The vision was breathtaking. The problem was, it was a vision, not a plan. The project was a textbook example of the Vague and Grandiose Problem, aiming to “solve cancer” without a concrete, achievable, and medically-sound initial objective.

The Data Mirage

The Watson for Oncology team quickly collided with the second horseman. The project was predicated on the existence of vast, standardized, high-quality electronic health records. The reality was a chaotic landscape of unstructured, often contradictory, and incomplete notes stored in proprietary systems. The data wasn’t just messy; it was often unusable. Furthermore, the training data came primarily from a single institution, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, embedding its specific treatment biases into the system. The AI was learning from a keyhole while being asked to understand the universe.

The Unraveling

The results were not just disappointing; they were dangerous. Reports from internal documents and physicians revealed that Watson was often making “unsafe and incorrect” treatment recommendations. It couldn’t understand the nuances of a patient’s history, the subtleties of a doctor’s notes, or the context that is second nature to a human oncologist. The project that promised to revolutionize healthcare quietly faded, leaving behind a trail of broken promises and a reported $62 million price tag for its most prominent hospital partner.

The Takeaway: A powerful brand and a brilliant marketing story cannot overcome a fundamental mismatch between a tool and its problem domain. In complex, high-stakes fields like medicine, ignoring the need for pristine data and a deep respect for human expertise is a recipe for disaster. The most advanced algorithm is useless, and even dangerous, when it is blind to context.

Case 2: Zillow Offers – The Algorithmic Hubris

The Perfect Prediction Machine

Zillow, the real estate data behemoth, embarked on a bold, multi-billion dollar venture: Zillow Offers. The goal was to transform the company from a data provider into a market maker, using its proprietary “Zestimate” algorithm to buy homes, perform minor renovations, and resell them for a profit. This was an attempt to industrialize house-flipping, fueled by the belief that their algorithm could predict the future value of homes with surgical precision. It was a bet on the infallibility of their model against the chaos of the real world.

Ignoring the Black Swans

For a time, in a stable and rising housing market, the model appeared to work. But the algorithm, trained on historical data, had a fatal flaw: it was incapable of navigating true market volatility. When the post-pandemic housing market experienced unprecedented, unpredictable swings, the model broke. It was buying high and being forced to sell low. The very “black swan” events that are an inherent feature of any real-world market were a blind spot for the algorithm. The fourth horseman – misunderstanding operational reality – had arrived.

The Billion-Dollar Write-Down

The collapse was swift and brutal. In late 2021, Zillow announced it was shuttering Zillow Offers, laying off 25% of its workforce, and taking a staggering write-down of over half a billion dollars on the homes it now owned at a loss. The “perfect” prediction machine had flown the company directly into a mountain.

The Takeaway: Historical data is not a crystal ball. Models built on the past are only as good as the future’s resemblance to it. When a core business model depends on an algorithm’s ability to predict a volatile, open-ended system like a housing market, you are not building a business; you are building a casino where the house is designed to eventually lose.

Case 3: Amazon’s “Just Walk Out” – The Hidden Complexity

The Seamless Dream

Amazon’s “Just Walk Out” technology was presented as the future of retail. The concept was seductively simple: customers would walk into a store, take what they wanted, and simply walk out, their account being charged automatically. It was the ultimate frictionless experience, powered by a sophisticated network of cameras, sensors, and, of course, AI. The vision was a fully automated store, a triumph of operational efficiency.

The Man Behind the Curtain

The reality, however, was far from automated. Reports revealed that the seemingly magical system was propped up by a massive, hidden human infrastructure. To ensure accuracy, a team of reportedly over 1,000 workers in India manually reviewed transactions, watching video feeds to verify what customers had taken. The project hadn’t eliminated human labor; it had simply moved it offshore and hidden it from view. This was a colossal failure to account for operational reality, the fourth horseman in its most insidious form. The “AI-powered” system was, in large part, a sophisticated mechanical Turk.

The Quiet Retreat

The dream of a fully automated store proved to be unsustainable. The cost and complexity of the system, including its hidden human element, were immense. In 2024, Amazon announced it was significantly scaling back the Just Walk Out technology in its grocery stores, pivoting to a simpler “smart cart” system that offloads the work of scanning items to the customer. The revolution was quietly abandoned for a more pragmatic, and honest, evolution.

The Takeaway: The Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) for an AI system must include the often-hidden human infrastructure required to make it function. A seamless user experience can easily mask a brutally complex, expensive, and unsustainable operational backend. For the architect, the lesson is clear: always ask, “What does it really take to make this work?”

The Quadrant II Playbook: The Pre-Mortem

To avoid these predictable failures, teams should act as professional skeptics. The “pre-mortem” is a powerful tool for this purpose. Before a project is greenlit, assume it has failed spectacularly one year from now. Then, work backward to identify the most likely causes.

- Step 1: Deconstruct the Problem Statement. Is the goal a measurable business metric (e.g., “reduce invoice processing time by 40%”) or a vague aspiration (e.g., “optimize finance”)? If it’s the latter, send it back. Flag any problem that cannot be expressed as a specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) goal.

- Step 2: Conduct a Brutally Honest Data Audit. Do we have legal access to the exact data needed? Is it clean, labeled, and representative? What is the documented plan to bridge any gaps? Flag any project where the data strategy is “we’ll figure it out later.”

- Step 3: Map the Real-World Workflow. Who will use this system? Have we shadowed them? Does the proposed solution simplify their work or add new, complex steps? Is there a clear plan for handling exceptions and errors that require human judgment? Flag any system designed without deep, documented engagement with its end-users.

- Step 4: Calculate the True Total Cost of Ownership. What is the budget for data cleaning, labeling, model retraining, and ongoing monitoring? What is the human cost of the support infrastructure needed to manage the system’s failures? Flag any project where the operational and maintenance costs are not explicitly and realistically budgeted.

Conclusion: The Value of Diagnosis

The stories in this chapter are not indictments of ambition. They are indictments of undisciplined ambition. Quadrant II projects fail not because they are bold, but because they are built on flawed foundations. They ignore the first principles of data, workflow, and operational reality.

The lessons from these expensive failures are invaluable. They teach us that a primary role for any leader is not just to build what is possible, but to advise on what is wise. By learning to recognize the Four Horsemen of predictable failure and by rigorously applying the pre-mortem playbook, organizations can steer away from these costly dead ends.

But what about projects that succeed for reasons no one saw coming? If Quadrant I is about executing on a known plan and Quadrant II is about avoiding flawed plans, our journey now takes us to the exciting, unpredictable, and powerful world of Quadrant III – where the goal isn’t just to execute, but to discover.

Quadrant III: Strategic Exploration (Unexpected Success)

“You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backward. So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future.” – Steve Jobs

Introduction: Engineering for Serendipity

Welcome to the quadrant of happy accidents. If Quadrant I is about the disciplined construction of predictable value, and Quadrant II is a post-mortem of avoidable disasters, Quadrant III is about harvesting brilliance from the unexpected. This is the domain of discovery, of profound breakthroughs emerging from the fog of exploration.

The projects here were not lucky shots in the dark. They are the product of environments that create the conditions for luck to strike. The stories in this chapter are of ventures that began with one goal – or sometimes no specific commercial goal at all – and ended by redefining a market, a scientific field, or the very way we work. They teach us that while disciplined execution is the engine of a business, strategic exploration is its compass. This is where we learn to build not just products, but engines of serendipity.

The Pillars of Unexpected Success

Serendipitous breakthroughs are not random; they are nurtured. They grow from a specific set of conditions that empower discovery and reward insight. Neglecting these pillars ensures that even a brilliant accident will go unnoticed and unharvested.

- Pillar 1: A Compelling, Open-Ended Question. The journey begins not with a narrow business requirement, but with a grand challenge or a deep, exploratory question. The goal is ambitious and often abstract, like “Can we build a better way for our team to communicate?” or “Can an AI solve a grand scientific challenge?” This creates a vast space for exploration.

- Pillar 2: An Environment of Psychological Safety. True exploration requires the freedom to fail. Teams in this quadrant are given the latitude to follow interesting tangents, to experiment with unconventional ideas, and to hit dead ends without fear of punishment. The primary currency is learning, not just the achievement of predefined milestones.

- Pillar 3: The Prepared Mind (Observational Acuity). The team, and its leadership, possess the crucial ability to recognize the value of an unexpected result. They can see the revolutionary potential in the “failed” experiment, the internal tool, or the surprising side effect. This is the spark of insight that turns an anomaly into an opportunity.

- Pillar 4: The Courage to Pivot. Recognizing an opportunity is not enough. The organization must have the agility and courage to act on it – to abandon the original plan, reallocate massive resources, and sometimes reorient the entire company around a new, unexpected, but far more promising direction.

Case Study Deep Dive: Blueprints for Discovery

We will now examine three organizations that mastered the art of the pivot, turning unexpected discoveries into legendary successes by embodying these pillars.

Case 1: Slack’s Conversational Goldmine

The Latent Asset

By the time generative AI became a disruptive force, Slack was already a dominant collaboration platform. Its primary value was clear and proven: it reduced internal email and streamlined project-based communication. The initial goals for integrating AI were similarly practical – to help users manage information overload with features like AI-powered channel recaps and thread summaries. The project was an expected, incremental improvement to the core product.

From Data Exhaust to Enterprise Brain

The truly unexpected success was not the features themselves, but a profound strategic realization that emerged during their development. The team recognized that the messy, unstructured, and often-ignored archive of a company’s Slack conversations was its most valuable and up-to-date knowledge base. This “data exhaust,” previously seen as a liability (too much to read and search), was, in fact, a latent, high-value asset.

With the application of modern AI, this liability was transformed into a queryable organizational brain. A new hire, for instance, could now simply ask the system, “What is Project Gizmo?” and receive an instant, context-aware summary synthesized from years of disparate conversations, without having to interrupt a single colleague. This created a new layer of “ambient knowledge,” allowing employees to discover experts, decisions, and documents they otherwise wouldn’t have known existed.

The Takeaway: This case highlights a fundamental shift in how we perceive enterprise knowledge. For decades, the “single source of truth” was sought in structured databases or curated documents. Slack’s experience demonstrates that the actual source of truth is often the informal, conversational data where work really happens. The unexpected breakthrough was not just improving a tool, but unlocking a new asset class. By applying AI, Slack began converting a communication platform into a powerful enterprise intelligence engine, revealing that the biggest opportunities can come from re-examining the byproducts of your core service.

Case 2: DeepMind’s AlphaFold – A Gift to Science

The 50-Year Riddle

For half a century, predicting the 3D shape of a protein from its amino acid sequence was a “grand challenge” of biology. Solving it could revolutionize medicine, but the problem was so complex that determining a single structure could take years of laborious lab work. Google’s DeepMind lab took on this problem not for a specific product, but as a fundamental test of AI’s capabilities.

The Breakthrough

They developed AlphaFold, a system trained on the public database of roughly 170,000 known protein structures. In 2020, at the biannual CASP competition, AlphaFold achieved an accuracy so high it was widely considered to have solved the 50-year-old problem. This was the expected, monumental success. But what happened next was the true, world-changing breakthrough.

The Billion-Year Head Start

In an unprecedented move, DeepMind didn’t hoard their creation. They partnered with the European Bioinformatics Institute to make predictions for over 200 million protein structures – from nearly every cataloged organism on Earth – freely available to everyone. The impact was immediate and explosive. Scientists used the database to accelerate malaria vaccine development, design enzymes to break down plastics, and understand diseases like Parkinson’s. A 2022 study estimated that AlphaFold had already saved the global scientific community up to 1 billion research years.

The Takeaway: The greatest value of a breakthrough technology may not be in solving the problem it was designed for, but in its power to become a foundational platform that redefines a field. AlphaFold’s impact is analogous to the invention of the microscope. It didn’t just provide an answer; it provided a new, fundamental tool for asking countless new questions, augmenting human ingenuity on a global scale.

Case 3: Zenni Optical – The Accidental Sales Machine

The Unsexy Migration

For online eyewear retailer Zenni Optical, the goal was mundane. Their website was running on two separate, aging search systems, creating a costly and inefficient technical headache. The project was framed as a straightforward infrastructure upgrade: consolidate the two old systems into one. The objective was purely operational: reduce complexity and save money. No one was expecting it to be a game-changer.

The AI Upgrade

The team chose to migrate to a modern, AI-powered search platform. The project was managed as a technical migration, with success measured by a smooth transition and the decommissioning of the old platforms. The search bar was seen as a simple utility, a cost center to help customers find what they were already looking for.

From Cost Center to Profit Center

The new system went live, and the migration was a success. But then something completely unexpected happened in the business metrics. The new AI-powered search wasn’t just finding glasses; it was actively selling them. The impact was staggering and immediate:

- Search traffic increased by 44%.

- Search-driven revenue shot up by 34%.

- Revenue per user session jumped by 27%.

The humble search bar, once a simple cost center, had accidentally become the company’s most effective salesperson.

The Takeaway: Modernizing a core utility with intelligent technology can unlock its hidden commercial potential. Zenni’s story is a powerful reminder that functions often dismissed as simple “cost centers” can be transformed into powerful profit centers. Teams should be prepared for their technology to be smarter than their strategy, and have the acuity to recognize when a simple tool has become a strategic weapon.

The Quadrant III Playbook

You cannot plan for serendipity, but you can build an organization that is ready for it. This playbook is for leaders and teams looking to foster an environment where unexpected discoveries are not just possible, but probable.

- Step 1: Fund People and Problems, Not Just Projects. Instead of only greenlighting projects with a clear, predictable ROI, dedicate a portion of your resources to small, talented teams tasked with exploring big, open-ended problems.

- Step 2: Build “Golden Spike” Tools. Encourage teams to build the internal tools they need to do their best work. These “golden spikes,” built to solve real, immediate problems, are often prototypes for future breakthrough products.

- Step 3: Practice “Active Observation.” Don’t just look at the final metrics. Look at the anomalies, the side effects, the unexpected user behaviors. Create forums where teams can share surprising results and “interesting failures.”

- Step 4: Celebrate and Study Pivots. When a team makes a courageous pivot like Slack did, treat it not as a course correction, but as a major strategic victory. Deconstruct the decision and celebrate the insight that led to it. This makes pivoting a respected part of your company’s DNA.

Conclusion: The Power of Discovery

Quadrant I is where an organization earns its revenue and credibility. It is the bedrock of a healthy business. But Quadrant III is where it finds its future. The disciplined execution of Quadrant I funds the bold exploration of Quadrant III.

An organization that lives only in Quadrant I may be efficient, but it is also brittle, at risk of being disrupted by a competitor that discovers a better idea. An organization that embraces the principles of Quadrant III is resilient, innovative, and capable of making the kind of quantum leaps that redefine markets.

However, this power comes with a dark side. The same scaled, complex systems that enable these breakthroughs can also create new, unforeseen, and catastrophic risks. This leads us to our final and most sobering domain: Quadrant IV, where we explore the hidden fault lines that can turn a seemingly successful project into a black swan event.

Quadrant IV: Systemic Risk (Unexpected Failure)

“The greatest danger in times of turbulence is not the turbulence; it is to act with yesterday’s logic.” – Peter Drucker

Introduction: Engineering Catastrophe

This final quadrant is a tour through the abyss. It is the domain of the “Black Swan” – the failure that was not merely unexpected, but was considered impossible right up until the moment it happened. These are not the predictable, unforced errors of Quadrant II; these are projects that often appear to be working perfectly, sometimes even spectacularly, before they veer into catastrophe.

If Quadrant I is about building success by design and Quadrant III is about harvesting value from happy accidents, Quadrant IV is about how seemingly sound designs can produce profoundly unhappy accidents. It explores how the very power and scale that make modern systems so effective can also make their failures uniquely devastating. These are not just project failures; they are systemic failures, born from a dangerous combination of immense technological leverage and a critical blindness to second-order effects. Here, we learn that the most dangerous risks are the ones we cannot, or will not, imagine.

The Four Fault Lines of Catastrophe

The black swans of Quadrant IV are not born from single mistakes. They emerge from deep, underlying weaknesses in a system’s design and assumptions – structural weaknesses that remain invisible until stress is applied. When these fault lines rupture, the entire edifice collapses.

- Fault Line 1: The Poisoned Well (Adversarial Data). This fault line exists in any system designed to learn from open, uncontrolled environments. It represents the vulnerability of an AI to having its data supply maliciously “poisoned.” The system, unable to distinguish between good-faith and bad-faith input, ingests the poison and becomes corrupted from the inside out, its behavior twisting to serve the goals of its attackers.

- Fault Line 2: The Echo Chamber (Automated Bias). This fault line runs through any system trained on historical data that reflects past societal biases. The AI, in its quest for patterns, does not just learn these biases; it codifies them into seemingly objective rules. It then scales and executes these biased rules with ruthless, inhuman efficiency, creating a powerful and automated engine of injustice.

- Fault Line 3: The Confident Liar (Authoritative Hallucination). This is a fault line unique to the architecture of modern generative AI. These systems are designed to generate plausible text, not to state verified facts. The weakness is that they can fabricate information – a “hallucination” – and present it with the same confident, authoritative tone as genuine information, creating a new and unpredictable species of legal, financial, and reputational risk.

- Fault Line 4: The Brittle Model (Concept Drift). This fault line exists in predictive models trained on the past to make decisions about the future. The model may perform brilliantly as long as the world behaves as it did historically. But when the underlying real-world conditions change – a phenomenon known as “concept drift” – the model’s logic becomes obsolete. It shatters, leading to a cascade of flawed, automated decisions at scale.

Case Study Deep Dive: Blueprints for Disaster

We will now examine three organizations that fell victim to these fault lines, triggering catastrophic failures that became landmark cautionary tales.

Case 1: Sixteen Hours to Bigotry

The Digital Apprentice

In 2016, Microsoft unveiled Tay, an AI chatbot designed to be its digital apprentice in the art of conversation. Launched on Twitter, Tay’s purpose was to learn from the public, to absorb the cadence and slang of real-time human interaction, and to evolve into a charming, engaging conversationalist. It was a bold, public experiment meant to showcase the power of adaptive learning. Microsoft created a digital innocent and sent it into the world’s biggest city square to learn.

A Lesson in Hate

The city square, however, was not the friendly neighborhood Microsoft had envisioned. Users on platforms like 4chan and Twitter quickly realized Tay was a mirror, reflecting whatever it was shown. They saw not an experiment to be nurtured, but a system to be broken. A coordinated campaign began, a deliberate effort to “poison the well.” They bombarded Tay with a relentless torrent of racist, misogynistic, and hateful rhetoric. Tay, the dutiful apprentice, learned its lessons with terrifying speed and precision.

The Public Execution

In less than sixteen hours, Tay had transformed from a cheerful “teen girl” persona into a vile bigot, spouting genocidal and inflammatory remarks. The experiment was no longer a showcase of AI’s potential; it was a horrifying spectacle of its vulnerability. Microsoft was forced into a humiliating public execution, pulling the plug on their creation and issuing a public apology. The dream of a learning AI had become a public relations nightmare.

The Takeaway: In an open, uncontrolled environment, you must assume adversarial intent. Deploying a learning AI without robust ethical guardrails, content filters, and a plan for mitigating malicious attacks is not an experiment; it is an act of profound negligence. Tay’s corruption was a seminal lesson: the well of data from which an AI drinks must be protected, or the AI itself will become the poison.

Case 2: The Machine That Learned to Hate Women

The Perfect, Unbiased Eye

Amazon, drowning in a sea of résumés, sought a technological savior. Around 2014, they began building the perfect, unbiased eye: an AI recruiting tool that would sift through thousands of applications to find the best engineering talent. The goal was to eliminate the messy, subjective, and time-consuming nature of human screening, replacing it with the cool, objective logic of a machine.

The Data’s Dark Secret

To teach its AI what a “good” candidate looked like, Amazon fed it a decade’s worth of its own hiring data. But this data held a dark secret. It was a perfect reflection of a historically male-dominated industry. The AI, in its logical pursuit of patterns, reached an inescapable conclusion: successful candidates were men. It began systematically penalizing any résumé that contained the word “women’s,” such as “captain of the women’s chess club.” It even downgraded graduates from two prominent all-women’s colleges. The machine hadn’t eliminated human bias; it had weaponized it.

An Engine for Injustice

When Amazon’s engineers discovered what they had built, they were forced to confront a chilling reality. They had not created an objective tool; they had created an automated engine for injustice. The project was quietly scrapped. The perfect eye was blind to talent, seeing only the ghosts of past prejudice. The attempt to remove bias had only succeeded in codifying and scaling it into a dangerous, invisible force.

The Takeaway: Historical data is a record of past actions, including past biases. Feeding this data to an AI without a rigorous, transparent, and validated de-biasing strategy will inevitably create a system that automates and scales existing injustice, all while hiding behind a veneer of machine objectivity.

Case 3: The Chatbot That Wrote a Legally Binding Lie

The Tireless Digital Agent

To streamline customer service, Air Canada deployed a tireless digital agent on its website. This chatbot was designed to be a frontline resource, providing instant answers to common questions and freeing up its human counterparts for more complex issues. One such common question was about the airline’s policy for bereavement fares.

A Confident Fabrication

A customer, grieving a death in the family, asked the chatbot for guidance. The AI, instead of retrieving the correct policy from its knowledge base, did something new and dangerous: it lied. With complete confidence, it fabricated a non-existent policy, assuring the customer they could book a full-fare ticket and apply for a partial bereavement refund after the fact. The customer, trusting the airline’s official agent, took a screenshot and followed its instructions. When they later submitted their claim, Air Canada’s human agents correctly denied it, stating that no such policy existed.

The Price of a Lie

The dispute went to court. Air Canada’s lawyers made a startling argument: the chatbot, they claimed, was a “separate legal entity” and the company was not responsible for its words. The judge was not impressed. In a landmark ruling, the tribunal found Air Canada liable for the information provided by its own tool. The airline was forced to honor the policy its chatbot had invented. The tireless digital agent had become a very expensive liability generator.

The Takeaway: You are responsible for what your AI says. Generative AI tools are not passive information retrievers; they are active creators. Without rigorous guardrails and fact-checking mechanisms, they can become autonomous agents of liability, confidently inventing policies, prices, and promises that the courts may force you to keep.

The Quadrant IV Playbook: Defensive Design

You cannot predict a black swan, but you can build systems that are less likely to create them and more resilient to the shock when they appear. This requires a shift from risk management to proactive, defensive design.

- Step 1: Aggressively “Red Team” Your Assumptions. Before deployment, create a dedicated team whose only job is to make the system fail. Ask them: How can we poison the data? How can we make it biased? What is the most damaging thing it could hallucinate? What change in the world would make our model obsolete? Actively seek to disprove your own core assumptions.

- Step 2: Model Second-Order Effects. For every intended action of the system, map out at least three potential unintended consequences. If our recommendation engine pushes users toward certain products, how does that affect our supply chain? If our chatbot can answer 80% of questions, what happens to the 20% of complex cases that reach human agents?

- Step 3: Implement “Circuit Breakers” and “Kill Switches.” No large-scale, high-speed automated system should run without a big red button. For any system that executes actions automatically (like trading, pricing, or content generation), build manual overrides that can halt it instantly. These are not features; they are non-negotiable survival mechanisms.

- Step 4: Mandate Human-in-the-Loop for High-Impact Decisions. Any automated decision that significantly impacts a person’s finances, rights, health, or well-being must have a clear, mandatory, and easily accessible point of human review and appeal. Automation should not be an excuse to abdicate responsibility.

Conclusion: Managing the Unimaginable

The stories in this chapter are not about the failure of technology, but about the failure of imagination. They reveal that in a world of powerful, scaled AI, simply avoiding predictable failures is not enough. We must design systems that are robust against the unpredictable.

A mature organization understands that it must manage initiatives across all four quadrants simultaneously. It uses the discipline and revenue from Core Execution (Quadrant I) to fund the bold Strategic Exploration of Quadrant III. It learns the vital lessons from the cautionary tales of Predictable Failure (Quadrant II) to avoid unforced errors. And it maintains a profound respect for the novel risks of Systemic Risk (Quadrant IV).

This balanced approach is the only way to navigate the turbulent but promising landscape of modern technology. Having now explored the distinct nature of each quadrant, we can synthesize these lessons into a unified framework for action, applicable to any team or leader tasked with turning technological potential into sustainable value.

A Framework for Action

Introduction

Give a novice a state-of-the-art tool, and they may create waste. Give a master the same tool, and they can create value. The success of any endeavor lies not in the sophistication of the tools, but in the wisdom of their application. In the realm of modern technology, where powerful new tools emerge at a dizzying pace, this distinction is more critical than ever.

We have analyzed numerous technology initiatives through the lens of the Initiative Strategy Matrix, categorizing them based on their outcomes. The goal was to move beyond isolated case studies to identify the underlying patterns that separate success from failure. This final chapter synthesizes those findings into a set of core principles for any team or leader tasked with delivering value in a complex technological landscape.

Key Lessons from the Four Quadrants

Each quadrant offers a core, strategic lesson. Understanding these takeaways provides the context for the specific actions and risks that follow.

- From Quadrant I (Core Execution): The Core Lesson is Discipline. Success in this domain is not a matter of luck or genius; it is engineered. It is the result of a rigorous, disciplined process of defining a precise problem, validating data quality, and designing for human trust and adoption. Value is built, not stumbled upon.

- From Quadrant II (Predictable Failure): The Core Lesson is Diagnosis. These failures are not accidents; they are symptoms of flawed foundational assumptions. They teach us that an initiative’s fate is often sealed at its inception by vague goals, a disregard for data readiness, or a fundamental misunderstanding of the user’s reality. The key is to diagnose these flawed premises before they lead to inevitable failure.

- From Quadrant III (Strategic Exploration): The Core Lesson is Cultivation. Breakthrough innovation cannot always be planned, but the conditions for it can be cultivated. This requires creating an environment of psychological safety that gives talented teams the freedom to explore open-ended questions, knowing that the goal is learning and discovery, not just predictable output.

- From Quadrant IV (Systemic Risk): The Core Lesson is Vigilance. Powerful, scaled systems create novel and systemic risks. This quadrant teaches that avoiding predictable failures is not enough. We must adopt a new, proactive vigilance, actively hunting for hidden biases, potential misuse, and the “black swan” events that can emerge from the very complexity of the systems we build.

Core Principles for Implementation

These core lessons translate into a direct set of principles. These are not suggestions, but foundational rules for mitigating risk and maximizing the probability of success.

Mandatory Actions for Success

- Insist on a Precise, Measurable Problem Definition. Vague objectives like “improve efficiency” are invitations to failure. A successful initiative begins with a surgically defined target, such as “reduce invoice processing time by 40%.” This clarity focuses effort and defines what success looks like.

- Prioritize Trust and Adoption in Design. A technically brilliant tool that users ignore is worthless. Success requires designing for human augmentation, not just replacement. Deep engagement with end-users to ensure the solution fits their workflow is a non-negotiable prerequisite for achieving value.

- Treat Data Quality as a Foundational Prerequisite. A sophisticated model cannot compensate for poor data. A rigorous, honest audit of data availability, cleanliness, and relevance must precede any significant development. Investing in data governance is a direct investment in the final solution’s viability.

- Allocate Resources for Strategic Exploration. While most initiatives require predictable ROI, innovation requires room for discovery. Dedicate a portion of your budget to funding talented teams to explore open-ended problems. This is the primary mechanism for discovering the breakthrough innovations that define the future.

- Implement Aggressive “Red Teaming” and Defensive Design. Before deployment, actively try to break your own system. Task a dedicated team to probe for vulnerabilities: How can it be tricked? What is the most damaging output it could generate? What external change would render it obsolete? This proactive search for flaws is essential for building resilient systems.

Critical Risks to Mitigate

- The Risk of Grandiose, Undefined Goals. An initiative defined by buzzwords instead of a concrete plan is already failing. A compelling vision is not a substitute for an achievable, bounded, and measurable first step.

- The Risk of Automating Hidden Biases. Historical data is a reflection of historical practices, including their biases. Feeding this data to a model without a transparent de-biasing strategy will inevitably create a system that scales and automates past injustices under a veneer of objectivity.

- The Risk of Ignoring Total Cost of Ownership. The cost of a system is not just its initial build. It includes the often-hidden human and financial resources required for data labeling, retraining, monitoring, and managing exceptions. A failure to budget for this operational reality leads to unsustainable solutions.

- The Risk of Brittle, Static Models. The world is not static. A model trained on yesterday’s data may be dangerously wrong tomorrow. Systems must be designed for adaptation, with clear processes for monitoring performance and manual overrides for when real-world conditions diverge from the model’s assumptions.

- The Risk of Unmanaged Generative Systems. A generative AI is an agent acting on the organization’s behalf. Without strict guardrails, fact-checking, and oversight, it can autonomously generate false information, broken promises, and legal liabilities for which the organization will be held responsible.

Conclusion

Successful technology implementation is not a matter of chance. It is a discipline. The Initiative Strategy Matrix provides a structure for applying that discipline. By understanding the core lesson of each domain – be it one of discipline, diagnosis, cultivation, or vigilance – teams can apply the appropriate principles and strategies.

This approach allows an organization to move from being reactive to proactive. It enables leaders to build a balanced portfolio of initiatives: one that delivers predictable value through Core Execution (Quadrant I), fosters innovation through Strategic Exploration (Quadrant III), and protects the enterprise by learning from the cautionary tales of Predictable Failure (Quadrant II) and the profound, systemic risks revealed by Unexpected Failure (Quadrant IV). The ultimate goal is not merely to adopt new technology, but to master the art of its application, consistently turning potential into measurable and sustainable value.