The Multi-Billion Dollar Wake-Up Call

In 2018, Netflix was drowning in their own success. With 230 million global subscribers generating 450+ billion daily events (viewing stops, starts, searches, scrolls), their engineering team faced a brutal reality: traditional application patterns were failing spectacularly at data scale.

Here’s what actually broke:

Problem 1: Database Meltdowns

Netflix’s recommendation engine required analyzing viewing patterns across 15,000+ title catalog. Their normalized PostgreSQL clusters—designed for fast individual user lookups—choked on analytical queries spanning millions of viewing records. A single “users who watched X also watched Y” query could lock up production databases for hours.

Problem 2: Storage Cost Explosion

Storing detailed viewing telemetry in traditional RDBMS format cost Netflix approximately $400M annually by 2019. Every pause, rewind, and quality adjustment created normalized rows across multiple tables, with storage costs growing exponentially as international expansion accelerated.

What Netflix discovered: data problems require data solutions, not application band-aids.

Their platform team made two fundamental architectural shifts that saved them billions:

Technical Change #1: Keystone Event Pipeline

- Before: Real-time writes to normalized databases, batch ETL jobs for analytics

- After: Event-driven architecture with Apache Kafka streams, writing directly to columnar storage (Parquet on S3)

- Impact: 94% reduction in storage costs, sub-second recommendation updates

Technical Change #2: Data Mesh Implementation

- Before: Centralized data warehouse teams owning all analytical data

- After: Product teams own their domain data as first-class products (viewing data, content metadata, billing data as separate meshes)

- Impact: Analytics development cycles dropped from months to days

The Bottom Line: Netflix’s shift from application-centric to data-centric architecture delivered measurable results—over $1.2 billion in infrastructure savings between 2019-2023, plus recommendation accuracy improvements that directly drove subscriber retention worth billions more.

Why DMBOK Matters (And Why Your Java Skills Won’t Save You)

Here’s where the Data Management Body of Knowledge (DMBOK) becomes your survival guide. While application frameworks focus on building software systems, DMBOK tackles data’s unique technical demands—problems that would make even senior developers weep into their coffee.

DMBOK knowledge areas address fundamentally different challenges: architecting systems for analytical scanning vs. individual record retrieval; designing storage that handles schema evolution across diverse sources; implementing security that balances data exploration with access control.

We’ll examine five core DMBOK domains where data demands specialized approaches: Data Architecture (data lakes vs. application databases), Data Storage & Operations (analytical vs. transactional performance), Data Integration (flexibility vs. rigid interfaces), Data Security (exploration vs. protection), and Advanced Analytics (unpredictable query patterns at scale).

Let’s dive into the specific technical domains where data demands its own specialized toolkit…

1. Data Architecture: Beyond Application Blueprints

If you ask a software architect to design a data platform, they might instinctively reach for familiar blueprints: normalized schemas, service-oriented patterns, and the DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) principle. This is a recipe for disaster. Data isn’t just a bigger application; it’s a different beast entirely, and it demands its own zoo.

When Application Thinking Fails at Data Scale

Airbnb learned this the hard way. Facing spiraling cloud costs and sluggish performance, they discovered their application-centric data architecture was the culprit. Their normalized schemas, perfect for transactional integrity, required over 15 table joins for simple revenue analysis, turning seconds-long queries into hour-long coffee breaks. Their Hive-on-S3 setup suffered from metastore bottlenecks and consistency issues, leading to a painful but necessary re-architecture to Apache Spark and Iceberg. The result? A 70% cost reduction and a platform that could finally keep pace with their analytics needs. The lesson was clear: you can’t fit a data whale into an application-sized fishbowl.

The Data Duplication Paradox: Why Data Engineers Love to Copy

In software engineering, duplicating code or data is a cardinal sin. In data engineering, it’s a core strategy called the Medallion Architecture. This involves creating Bronze (raw), Silver (cleansed), and Gold (aggregated) layers of data. It’s like a data distillery: the raw stuff goes in, gets refined, and comes out as top-shelf, business-ready insight.

Uber uses this pattern for everything from ride pricing to safety analytics. Raw GPS pings land in the Bronze layer, get cleaned and joined with trip data in Silver, and become aggregated demand heatmaps in the Gold layer. This intentional “duplication” enables auditability, quality control, and sub-second query performance for dashboards—things a normalized application database could only dream of.

A Tour of Data-Specific Architectural Patterns

The evolution of data architecture is a story of increasing abstraction and specialization, moving from rigid structures to flexible, federated ecosystems.

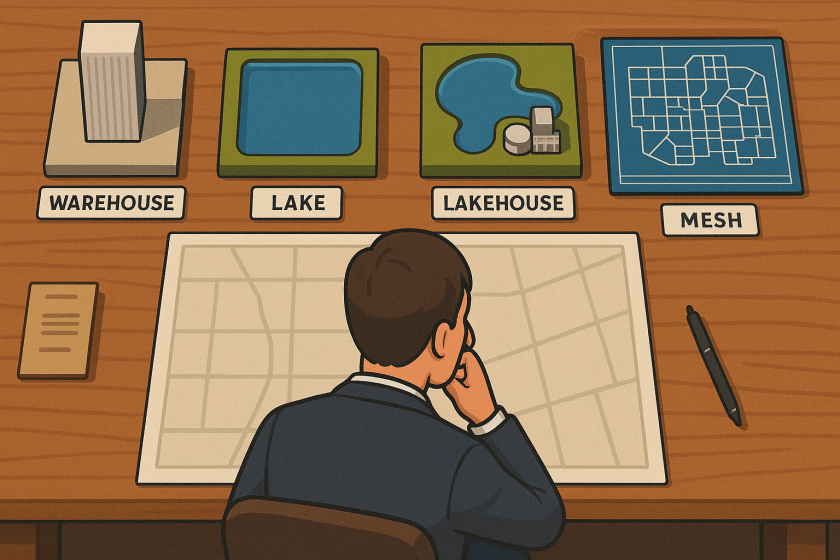

The Data Warehouse: Grand Central Station for Analytics

A Data Warehouse (DW) is a centralized repository optimized for structured, analytical queries. It’s the classic, buttoned-down choice for reliable business intelligence, ingesting data from operational systems and remodeling it for analysis, typically in a star schema. It differs from a Data Lake by enforcing a schema before data is written, ensuring high quality at the cost of flexibility. For example, Amazon’s retail operations rely on OLTP databases like Aurora for transactions, but all analytical heavy lifting happens in their Redshift data warehouse.

The Data Lake: The “Anything Goes” Reservoir

A Data Lake is a vast storage repository that holds raw data in its native format until it’s needed. It embraces a schema-on-read approach, offering maximum flexibility to handle structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data. This flexibility is its greatest strength and its greatest weakness; without proper governance, a data lake can quickly become a data swamp. Spotify’s platform, which ingests over 8 million events per second at peak, uses a data lake on Google Cloud to capture every user interaction before it’s processed for analysis.

The Data Lakehouse: The Best of Both Worlds

A Data Lakehouse merges the flexibility and low-cost storage of a data lake with the data management and ACID transaction features of a data warehouse. It’s the mullet of data architecture: business in the front (warehouse features), party in the back (lake flexibility). Netflix’s migration of 1.5 million Hive tables to an Apache Iceberg-based lakehouse is a prime example. This move gave them warehouse-like reliability on their petabyte-scale S3 data lake, solving consistency and performance issues that plagued their previous setup.

The Data Mesh: The Federation of Data Products

A Data Mesh is a decentralized architectural and organizational paradigm that treats data as a product, owned and managed by domain teams. It’s a response to the bottlenecks of centralized data platforms in large enterprises. Instead of one giant data team, a mesh empowers domains (e.g., marketing, finance) to serve their own high-quality data products. Uber’s cloud migration is powered by a service explicitly named “DataMesh,” which decentralizes resource management and ownership to its various business units, abstracting away the complexity of the underlying cloud infrastructure.

The Bottom Line: Data is Different

The core takeaway is that data architecture is not a sub-discipline of software architecture; it is its own field with unique principles.

- Applications optimize for transactions; data platforms optimize for questions.

- Applications hide complexity; data platforms expose lineage.

- Applications scale for more users; data platforms scale for more history.

The architectural decision that saved Airbnb 70% in costs wasn’t about writing better application code. It was about finally admitting that when it comes to data, you need a bigger, and fundamentally different, boat.

2. Data Storage & Operations: The Unseen Engine Room

If your data architecture is the blueprint, then your storage and operations strategy is the engine room—a place of immense power where the wrong choice doesn’t just slow you down; it can melt the entire ship. An application developer’s favorite database, chosen for its speed in handling single user requests, will invariably choke, sputter, and die when asked to answer a broad analytical question across millions of users. This isn’t a failure of the database; it’s a failure of applying the wrong physics to the problem.

OLTP vs. OLAP: A Tale of Two Databases

The world of databases is split into two fundamentally different universes: Online Transaction Processing (OLTP) and Online Analytical Processing (OLAP). Mistaking one for the other is a catastrophic error.

- OLTP Databases (The Sprinters): These are the engines of applications. Think PostgreSQL, MySQL, Oracle, or Amazon Aurora. They are optimized for thousands of small, fast, predictable transactions per second—updating a single customer’s address, processing one order, recording a single ‘like’. They are built for transactional integrity and speed on individual records.

- OLAP Databases (The Marathon Runners): These are the engines of analytics. Think Snowflake, Google BigQuery, Amazon Redshift, or Apache Druid. They are optimized for high-throughput on massive, unpredictable queries—scanning billions of rows to calculate quarterly revenue, joining vast datasets to find customer patterns, or aggregating years of historical data.

Nowhere is this split more critical than in finance. JPMorgan Chase runs its core banking operations on high-availability OLTP systems to process millions of daily transactions with perfect accuracy. But for risk analytics, they leverage a colossal 150+ petabyte analytical platform built on Hadoop and Spark. Asking their core banking system to calculate the firm’s total market risk exposure would be like asking a bank teller to manually count every dollar bill in the entire U.S. economy. It’s not what it was built for. The two systems are architected for opposing goals, and the separation is non-negotiable for performance and stability.

Column vs. Row Storage: The Billion-Row Scan Secret

This OLAP/OLTP split dictates how data is physically stored, a choice that has 1000x performance implications.

- Row-Based Storage (For Applications): OLTP databases like PostgreSQL store data in rows. All information for a single record (

customer_id,name,address,join_date) is written together. This is perfect for fetching one customer’s entire profile quickly. - Columnar Storage (For Analytics): OLAP databases like Snowflake use columnar storage. All values for a single column (e.g., every

join_datefor all customers) are stored together. This seems inefficient until you ask an analytical question: “How many customers joined in 2023?” A columnar database reads only thejoin_datecolumn, ignoring everything else. A row-based system would be forced to read every column of every customer record, wasting staggering amounts of I/O.

The impact is profound. Facebook saw 10-30% storage savings and corresponding query speed-ups just by implementing a columnar format for its analytical data. A financial firm cut its risk calculation times from 8 hours to 8 minutes by switching to a columnar platform. The cost savings are just as dramatic. Netflix discovered that storing event history in columnar Apache Iceberg tables was 38 times cheaper than in row-based Kafka logs, thanks to superior compression (grouping similar data types together) and I/O efficiency.

SLA and Stability: The Pager vs. The Dashboard

Application developers live by the pager, striving for 99.999% uptime and immediate data consistency. If a user updates their profile, that change must be reflected instantly.

Analytical platforms operate under a different social contract. While stability is crucial, the definition of “up” is more flexible. It is perfectly acceptable for an analytics dashboard to be five minutes behind real-time. This concept, eventual consistency, is a core design principle. The priority is throughput and cost-effectiveness for large-scale data processing, not sub-second transactional guarantees.

Uber exemplifies this by routing queries to different clusters based on their profile. A machine learning model predicts a query’s runtime; short, routine queries are sent to a low-latency “Express” queue, while long, exploratory queries go to a general-purpose cluster. This ensures that a data scientist’s heavy, experimental query doesn’t delay a city manager’s critical operational dashboard. It’s a pragmatic acceptance that not all data questions are created equal, and the platform’s operational response should reflect that.

Unlike Traditional Software Development…

- Latency vs. Throughput: Applications prioritize low latency for user interactions. Data platforms prioritize high throughput for massive data scans.

- Operations: Application databases (e.g.,

PostgreSQL) are optimized for CRUD on single records. Analytical databases (e.g.,Snowflake,BigQuery) are optimized for complex aggregations across billions of records.- Consistency: Applications demand immediate consistency. Analytics thrives on eventual consistency, trading sub-second precision for immense analytical power.

The bottom line is that the physical and operational realities of storing and processing data at scale are fundamentally different from those of application data. The tools, the architecture, and the mindset must all adapt to this new reality.

3. Data Integration & Pipelines: Beyond Application APIs

In application development, integration often means connecting predictable, well-defined services through APIs. In the data world, integration is a far more chaotic and complex discipline. It’s about orchestrating data flows from a multitude of diverse, evolving, and often unreliable sources. This is the domain of Data Integration & Interoperability, where we must decide how to process data (ETL vs. ELT), when to process it (batch vs. streaming), and how to trust it (schema evolution and lineage). Applying application-centric thinking here doesn’t just fail; it leads to broken pipelines and eroded trust.

The How: ETL vs. ELT and the Logic Inversion

For decades, the standard for data integration was Extract-Transform-Load (ETL). This is a pattern familiar to application developers: you get data, clean and shape it into a perfect structure, and then load it into its final destination. It’s cautious and controlled. The modern data stack, powered by the cloud, flips this logic on its head with Extract-Load-Transform (ELT). In this model, you load the raw, messy data first into a powerful cloud data warehouse or lakehouse and perform transformations later, using the massive parallel power of the target system.

This inversion is a paradigm shift. Luxury e-commerce giant Saks replaced its brittle, custom ETL pipelines with an ELT approach. The result? They onboarded 35 new data sources in six months—a task that previously took weeks per source—and saw a 5x increase in data team productivity. European beauty brand Trinny London adopted an automated ELT process and eliminated so much manual pipeline management that it saved them over £260,000 annually. ELT thrives because it preserves the raw data for future, unforeseen questions and empowers analysts to perform their own transformations using SQL—a language they already know.

The When: Batch vs. Streaming and the Architecture of Timeliness

Application logic is often synchronous—a user clicks, the app responds. Data pipelines, however, must be architected for a specific temporal dimension:

- Batch Processing: Data is collected and processed in large, scheduled chunks (e.g., nightly). This is the workhorse for deep historical analysis and large-scale model training. It’s efficient but slow.

- Stream Processing: Data is processed continuously, event-by-event, as it arrives. This is the engine for real-time use cases like fraud detection, live recommendations, and IoT sensor monitoring.

Many modern systems require both. Uber’s platform is a prime example of a hybrid Lambda Architecture. Streaming analytics power sub-minute surge pricing adjustments and real-time fraud detection, while batch processing provides the deep historical trend analysis for city managers. They famously developed Apache Hudi to shrink the data freshness of their batch layer from 24 hours to just one hour, a critical improvement for their fast-moving operations. The pinnacle of real-time processing can be seen in media. Disney+ Hotstar leverages Apache Flink to handle massive live streaming events, serving over 32 million concurrent viewers during IPL cricket matches—a scale where traditional application request-response models are simply irrelevant.

The Trust: Schema Evolution and Data Lineage

Here lies perhaps the most profound difference from application development. An application API has a versioned contract; breaking it is a cardinal sin. Data pipelines face a more chaotic reality: schema drift, where upstream sources change structure without warning. A pipeline that isn’t designed for this is a pipeline that is guaranteed to break.

This is why modern data formats like Apache Iceberg are revolutionary. They are built to handle schema evolution gracefully, allowing columns to be added or types changed without bringing the entire system to a halt. When Airbnb migrated its data warehouse to an Iceberg-based lakehouse, this flexibility was a key driver, solving consistency issues that plagued their previous setup.

Furthermore, because data is transformed across multiple hops, understanding its journey—its data lineage—is non-negotiable for trust. When a business user sees a number on a dashboard, they must be able to trust its origin. In financial services, this is a regulatory mandate. Regulations like BCBS 239 require banks to prove the lineage of their risk data. Automated lineage tools are essential, reducing audit preparation time by over 70% and providing the transparency needed to satisfy regulators and build internal confidence.

Unlike Traditional Software Development…

- Integration Scope: Application integration connects known systems via stable APIs. Data integration must anticipate and handle unknown future sources and formats.

- Data Contracts: Applications process known, versioned data formats. Data pipelines must be resilient to constant schema evolution and drift from upstream sources.

- Failure Impact: A failed API call affects a single transaction. A data pipeline failure can corrupt downstream analytics for the entire organization, silently eroding trust for weeks.

Data integration is not a simple data movement task. It is a specialized engineering discipline requiring architectures built for scale, timeliness, and—most importantly—the ability to adapt to the relentless pace of change in the data itself.

4. Data Security: The Analytical Freedom vs. Control Dilemma

In application security, the rules are clear: a user’s role grants access to specific features. Data security is a far murkier world. The goal isn’t just to lock things down; it’s to empower exploration while preventing misuse. This creates a fundamental tension: granting analysts the freedom to ask any question versus the organization’s duty to protect sensitive information.

Access Control: From Roles to Rows and Columns

A simple role-based access control (RBAC) model, the bedrock of application security, shatters at analytical scale. An analyst’s job is to explore and join datasets in unforeseen ways. You can’t pre-define every “feature” they might need.

This is where data-centric security models diverge, controlling access to the data itself:

- Column-Level Security: Hides sensitive columns.

- Row-Level Security: Filters rows based on user attributes.

- Dynamic Data Masking: Obfuscates data on the fly (e.g.,

****@domain.com).

For example, a Fortune 500 financial firm uses these techniques in their Amazon Redshift warehouse. A sales rep sees only their territory’s data; a financial analyst sees only their clients’ accounts. In the healthcare sector, a startup’s platform enforces HIPAA compliance by allowing a doctor to see full details for their own patients, while a researcher sees only de-identified, aggregated data from the same tables. These policies are defined once in the data platform and enforced everywhere, a world away from hard-coding permissions in application logic.

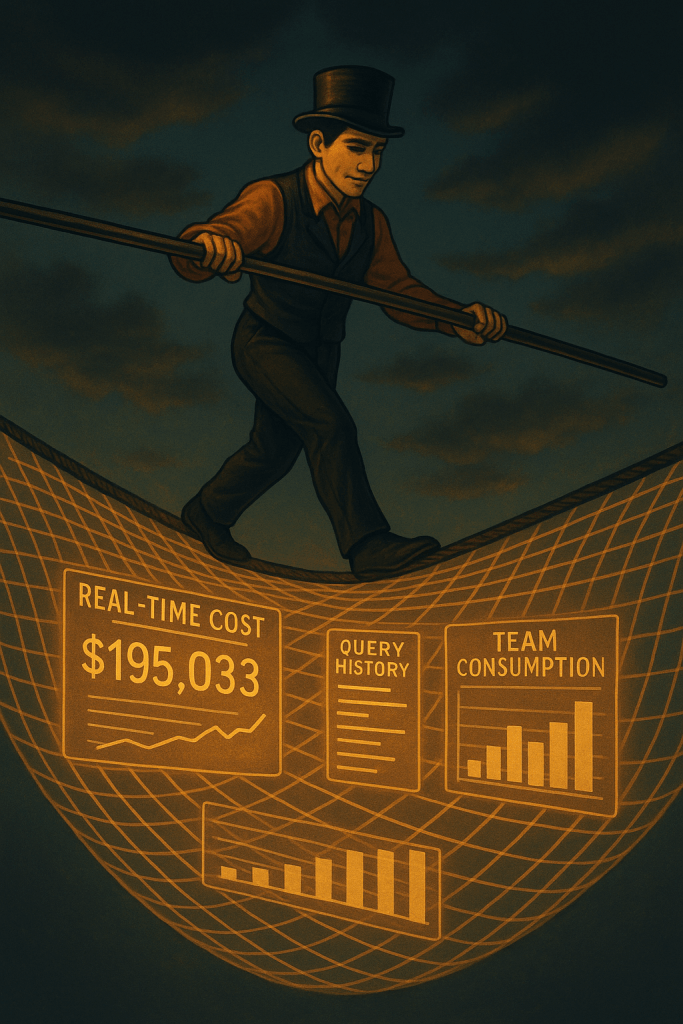

The Governance Tightrope: Enabling Exploration Safely

Application security protects against known threats accessing known functions. Analytical security must protect against unknown questions exposing sensitive patterns. A data scientist joining multiple large datasets could potentially re-identify anonymized individuals—a risk the original data owners never foresaw.

This requires a new model of governance that balances freedom with responsibility.

- Netflix champions a culture of “Freedom & Responsibility.” Instead of imposing strict quotas, they provide cost transparency dashboards. This nudges engineers to optimize heavy jobs and curb wasteful spending without stifling innovation.

- Uber’s homegrown DataCentral platform provides a holistic view of its 1M+ daily analytics jobs. It tracks resource consumption and cost by team, enabling chargeback and capacity planning. This provides guardrails and visibility, preventing a single team’s experimental query from impacting critical operations.

This is Privacy by Design, building governance directly into the platform. It requires collaboration between security, data engineers, and analysts to design controls that enable exploration safely, such as providing “data sandboxes” with anonymized data for initial discovery.

Unlike Traditional Software Development…

- Access Scope: Applications control access to functions. Data platforms control access to information.

- Granularity: Application security is often binary. Data security is contextual, granular, and dynamic.

- User Intent: Applications serve known users performing predictable tasks. Analytics serves curious users asking unpredictable questions.

The stakes are high. A single overly permissive analytics dashboard can expose more sensitive data than a dozen application vulnerabilities. The challenge is not just to build platforms that can answer any question, but to build them in a way that ensures only the right questions can be asked by the right people.

Conclusion: The Technical Foundation for Data Value

The journey through data’s specialized domains reveals a fundamental truth: the tools and architectures that power data-driven organizations are not merely extensions of traditional software engineering—they are a different species entirely. We’ve seen how applying application-centric thinking to data problems leads to costly failures, while embracing data-specific solutions unlocks immense value.

The core conflicts are now clear. Data Architecture must optimize for broad, unpredictable questions, not just fast transactions, a shift that allowed Airbnb to cut infrastructure costs by 70%. Data Storage & Operations demand marathon-running OLAP engines and columnar formats that can slash analytics jobs from 8 hours to 8 minutes. Data Integration requires pipelines built for chaos—resilient to schema drift and capable of boosting data team productivity by 5x through modern ELT patterns. Finally, Data Security must navigate the complex trade-off between analytical freedom and information control, a challenge that simple role-based permissions cannot solve. These are the technical realities codified by frameworks like the DMBOK, which provide the essential survival guide for this distinct landscape.

However, building this powerful technical foundation reveals a new challenge. It requires a new analyst-developer partnership, a collaborative model where data engineers, platform specialists, security experts, and data analysts work together not in sequence, but in tandem. They co-design the architectures, tune the pipelines, and define the security protocols. This convergence of skills—where engineering meets deep analytical and domain expertise—is the organizational engine that makes the technical toolkit run effectively.

But even the most advanced technology and the most collaborative teams are not enough. A perfectly architected lakehouse can still become a swamp. A lightning-fast pipeline can deliver flawed data. A flexible analytics platform can create massive security holes. Specialized technology enables data value, but it is the governance framework that makes it reliable, trustworthy, and sustainable.

Now that you understand why data demands a different technical approach than application development, let’s explore the governance frameworks that make these specialized tools truly effective.